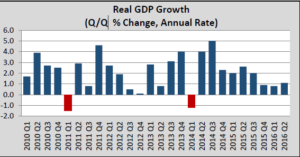

Recap: A divide at the heart of the U.S. economy – consumers ramped up spending while businesses pulled back – left overall economic growth stuck in the 1% range. Household outlays surged this spring at their strongest pace in a year and a half, but business investment declined for the third straight quarter. The result was a modest 1.1% annualized economic growth rate in the second quarter of 2016.

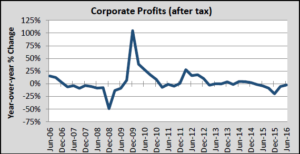

Company earnings also remained under pressure, restraining investment. A key measure of corporate profits rose 4.9% in the second quarter, but gains this year were not enough to offset the drop from last year. Second-quarter profits were down 2.2% compared with a year earlier.

Overall economic growth has been tepid since late last year, with GDP advancing at a modest pace of 0.9% in the fourth quarter of 2015 and 0.8% in the first quarter of 2016 and just over 1% in 2Q. Inventories have been a major drag on growth in the second quarter, but businesses may have better aligned their inventories with demand, which could boost growth in the near term. GDP growth should pick up in the third quarter.

Business fixed investment is also expected to begin growing again in the second half of 2016, though it will likely remain soft. As profits have stagnated, election-year uncertainty could also act as an additional constraint to capital expenditures.

Durable Goods: Durable goods orders in the U.S. increased 4.4% in July. This showed the beleaguered factory sector has regained some traction. The July surge in durable goods orders was partly attributable to orders for aircraft, which can be volatile. Motor vehicles and parts orders however held steady. Besides aircraft and autos, durable goods orders were still up 1.5%—the largest monthly gain since January. Shipments also picked up for the second month, but the strength came from defense spending, rather than the private sector. Core capital goods orders, which have tended to lead shipments, increased 1.6% in July, the largest one-month increase since January.

Durable goods inventories increased in July, marking the first increase of the year and the first hard data indication for third quarter inventories. After an outright decline in the second quarter, even a modest gain in inventories could add to economic growth in the third quarter.

Consumer Confidence Index: The consumer confidence index rose 4.4 points in August to 101.1. Consumers largely shrugged off remaining concerns about the Brexit vote and the temporary turmoil it caused. The stock market’s quick recovery seemed to have removed many of those fears. Moreover, strong employment reports also showed that the labor market was in good shape. Consumer spending grew at 4.4% in the second quarter.

All of these indicate that consumers feel fairly positive about the economy. Consumers will likely be the driving force behind the uptick of economic activity in the second half of 2016.

Small Business Optimism Index: The NFIB’s small business optimism index rose 0.1 points to 94.6 in July. Small business optimism recorded its fourth consecutive monthly gain, making up some of the lost ground earlier in the year. The NFIB report echoed recent data releases, particularly on the labor market side, that suggested modest economic growth with the domestic side of the economy remaining on a solid footing despite elevated global and political uncertainty.

Small business owners have remained skeptical about the future and have appeared reluctant to invest with their appetite additionally tempered by political uncertainty during an election year. On the other hand, businesses have remained keen to continue hiring with labor market tightness and quality of labor issues increasingly reported.

Income and job gains, along with the windfall from still low energy prices, should continue supporting consumer spending and shore up business confidence in the coming months.

Labor Market: The U.S. labor market has recently capped off the best two-month stretch of hiring so far this year, despite global turbulence and slower business spending. This has posed a challenge for the Federal Reserve as it aims to raise interest rates again in coming months, without spooking investors.

The latest figures have spurred relief after a dim first-half U.S. growth reading, falling corporate profits and retreating business spending. At least in the short term, the economy would appear to be on solid footing despite longer-run worries.

Firm employment gains have helped propel consumer spending, but an improving labor market doesn’t entirely square with other data showing a deep slowdown in overall economic growth since the end of 2015. Gross domestic product rose a meager 1% at a seasonally adjusted annual rate during the first half of the year.

American companies, dogged by shrinking profits, have cut investment for three straight quarters. Alongside steady hiring, that has led to slumping labor-productivity growth.

Inflation: Americans have faced little overall inflation pressure with gasoline and grocery prices falling, potentially giving the Federal Reserve more leeway to keep interest rates low for a longer period. Consumer prices remained unchanged in July (0.0% m/m), as lower energy prices offset a slight 0.1% increase in core inflation. The year-over-year pace of inflation was 0.8% at the end of July. Core inflation pressures cooled off a bit in July and the annual pace of core inflation remained at 2.2% y/y. Services have been a key source of inflation so far this year, in large part driven by the housing market.

Energy prices have continued to exert significant downward pressure on headline inflation, while core inflation, which had seen some upward momentum in recent months, took a bit of a breather. Headline inflation should hit 2% by year-end assuming oil prices continue to rise modestly. Core inflation, on the other hand, should maintain its current pace in 2016 as the tug of war between falling core goods prices and hotter core services inflation continues.

Inflation has not been a pressing concern for the Federal Reserve, but the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, the core personal consumption expenditure deflator, should gradually head higher in the coming months.

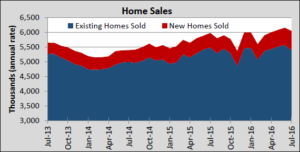

Housing: Homebuilding

has continued to gradually recover from the housing bust that accompanied the Great Recession. Sales of previously owned homes rose to their strongest pace since February 2007. New home sales also rose. Steadily rising demand has led to concerns about the low inventory of new and existing homes on the market, which has pushed up prices and could eventually weigh on further growth.

The housing recovery provided a tailwind for overall U.S. economic growth through most of 2014, 2015 and early 2016. However, a drop in residential fixed investment shaved 0.24 percentage point off the second quarter’s 1.2% annual growth rate for gross domestic product.

Residential construction rose in July to its highest level in five months, but a stall in building-permit issuance offered a possible sign of caution ahead among U.S. home builders. Also, tight inventories have remained a worry, and home sales may have softened in the second half of the year.

Housing starts increased by 25,000 units in June to 1.2 million (annualized). Most of the increase was concentrated in the multifamily segment, but the pace of single family homebuilding also rose modestly. Building permits declined slightly, marking the first decline following three consecutive monthly increases. Across regions, the monthly increase was broad-based, with the South, Northeast, and Midwest recording moderate to modest gains.

Both starts and permitting activity have been posting near post-recession highs, despite the near term slowdown in permitting, corroborating the view that homebuilding in America has continued on a modestly upward trajectory. Sales of newly built homes rose in July to their highest level in nearly a decade, a sign of solid momentum in the U.S. housing market. Purchases of new single-family homes rose 12.4% in July from a month earlier to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 654,000. These continued signs of demand for new homes have remained solid in a low interest rate, low unemployment environment.

Going forward, the homebuilding outlook should remain favorable, supported by historically low mortgage rates, a firming labor market and related wage gains for workers. The housing market should provide support for the U.S. economic recovery in the second half of 2016.

Fed: With this month’s job report, the Federal Reserve may be getting closer to achieving one of its dual mandates of bringing the economy to full employment. That alone, however, may not be enough for the central bank to start raising the interest rates.

Recent media reports have raised the possibility that the Fed would raise interest rates at its September meeting, although given policy makers’ caution, the odds probably favor a hold. With the Fed’s November meeting right up against the Presidential election, a December move would seem the more likely bet.

By December, the job market could be tighter. The amount of hiring needed just to keep up with US population growth is about 85,000 additional jobs a month. Over the past three months, the economy has been adding jobs more than twice as fast. If that pace should continue, plus some more part-time workers transitioning to full time, a 4.7% unemployment rate would put the labor market at full employment—consistent with the Fed’s 2% inflation target.

While that could give the Fed the comfort needed to raise rates in December, any rate increases that come after that would likely be gradual. With the relationship between the job market and consumer prices looking less certain than in the past, the Fed will want to see clear evidence that its 2% inflation target is within reach. What’s more, the Fed may be willing to let inflation run a little higher in order to ensure that its longer-run goal of 2% inflation really sticks.

Investors however don’t expect much in the way of either inflation or growth in the years to come, as of now. Current bond prices would imply low inflation and investor capital has been flooding into dividend-paying stocks, rather than shares of the cyclical companies that would most benefit from the economy running a little hot. The easing of inflation pressures seen in the consumer-price index, along with weak economic-output readings for the first half of the year, have reinforced the argument of some officials to wait on a rate increase. This fall’s U.S. presidential election will add uncertainly to the economic outlook and could make some policy makers cautious.

United Kingdom: The Bank of England (BoE) decided to lower interest rates for the first time since 2009, by 25 basis points, from 0.50 to 0.25, a historically low level for the target rate. At the same time, the BoE decided to increase its asset purchase program. The bank also said that it did not envision going the route of other European or Asian central banks when they decided to introduce negative interest rates.

The U.K. is likely headed for a mild recession at the end of this year and into the first quarters of next year. However, their economy should recover once some of the uncertainty regarding this new environment decreases and the new government decides what fiscal measures will be implemented to help during the transition out of the European Union. However, risks will remain as economic actors try to figure out what a European Union less the U.K. will look like in the future.

The U.K. Treasury may need to consider further steps to stimulate the economy to complement the BOE’s monetary steps. The central bank’s rate cut and bond purchases were aimed at lowering borrowing costs for households and businesses, and to encourage spending to keep economic growth moving forward. Ultra-low rates could be used by the government to finance spending on infrastructure to also stimulate the economy. Additional options to boost to the U.K. economy would include cutting the value-added tax, trimming corporate taxes, or increasing tax breaks for investment to spur corporate spending.

Japan: Japan’s government approved a new government stimulus package that included new spending, in its latest effort to jump-start their nation’s sluggish economy. The government will be pumping money into infrastructure projects. The package would also aim to offer more help to Japanese who haven’t benefitted from the last three years’ growth program. By total size, the stimulus package ranks among Japan’s biggest since the global financial crisis.

This spending plan is intended to bolster Japan’s economy amid concerns about global growth, particularly a slowdown in China, emerging markets and the effects of the U.K.’s decision to exit the European Union. Japan’s economy has swung between expansions and contractions in recent quarters.

This stimulus should modestly increase economic growth. Fiscal stimulus alone is not likely to create sustainable growth as more structural changes in the Japanese economy, such as, deregulation in sectors including agriculture, medical services, education and business fields, are needed.

Outlook: Volatility in the economic data and policy signals persist in an economy that continued to trend at a moderate growth pace with slow but rising inflation and a cautious U.S. central bank. A great divide in the economy has persisted with strength in consumer spending and housing set against weakness in business investment, net exports and a significant inventory correction.

Meanwhile, inflation has continued to inch upward. Given the modest inflation pace and global uncertainties, the yield curve has remained relatively flat. This combination of disappointing growth and continued moderate inflation should provide the Fed a basis for raising the fed funds rate—but without any sense of urgency. A December rate increase by the Fed would seem the most likely.

The outlook for economic growth should remain weak outside the U.S., representing another potential drag to US economic activity. Last month, the International Monetary Fund downgraded its forecast yet again for global economic growth, after Britain’s vote to leave the European Union weighed on consumer confidence and investor sentiment.

An apparent inconsistency could remain strikingly clear —the willingness of companies to absorb the high cost of labor, yet completely shut down their capital spending—illustrating how cautious CEOs remain about large scale investments for the future given the uncertainties about the U.S. election, the fallout from Brexit, and the health of the global economy.

Fed officials will have to assess these crosscurrents as they consider making only the second increase to the central bank’s benchmark interest rate since 2006. Policy makers boosted rates last December but have since held off amid uncertain risks and volatile markets. The question at this point for them remains, which data point is more telling of the underlying momentum in the economy: an average 1% GDP or an average of 200,000 payrolls? Until the Fed answers that question with confidence, caution will remain the name of the game.