Recap: Gross domestic product rose at a 2.1% seasonally adjusted annual rate in the July-to-September period, up from an initial estimate of 1.5% growth. The revision was largely due to a smaller drag from private inventories as companies did not let their stockpiles dwindle as much as initially estimated.

The upward revision to economic growth was offset by weaker details, with slightly slower domestic demand growth and more drag from net exports, making up for the smaller draw down in inventories. Despite the upgrade to third-quarter economic performance, the growth pace marked a sharp slowdown from the second quarter, when the economy expanded at a 3.9% rate.

U.S. employers added jobs in October at the quickest pace this year, while boosting wages at the fastest rate since 2009, giving the Federal Reserve its clearest signal yet that the economy may be strong enough to withstand an interest-rate increase in December. The labor market report eased fears that market turmoil and slowing growth in China and Europe were crimping the U.S. economy.

Fed officials have said for months they would lift their benchmark rate, which has been near zero since late 2008, after they saw more improvement in the labor market and felt “reasonably confident” about annual inflation. Even the most diehard doves on the Fed would be hard pressed to ignore the recent employment report. Firms have many job openings and have been having trouble filling vacancies.

In financial markets, investors have begun adjusting to the possibility of a December rate increase.

Consumer Confidence: Consumer confidence fell hard in November, with the overall index declining 8.7 points to 90.4, its lowest level since July 2014. The drop was evident in both the present situation index and the expectations series. The decline appeared to be driven by economic concerns. Consumer confidence has tended to be fickle on a monthly basis but 90.4 represented a level consistent with solid gains in consumer spending and overall economic growth; it was, however, a caution flag for the Fed.

Housing: Housing starts tumbled 11.0 percent to a 1.06 million-unit pace in October, with declines registered in both single- and multifamily starts. Much of October’s drop occurred in the volatile multifamily component, which plummeted 25.1%. Permits increased during the month and now show the level running ahead of starts, which would suggest some payback could be in store in the coming months. Moreover, the trend in starts still showed an upward trend, as the three month moving average registered a 1.13 million unit pace.

New home sales increased at a 495,000-unit rate in October, having rebounded strongly from the downwardly revised September figure. The three-month moving average downshifted to a 485,000-unit pace, the lowest level since December of last year. With the exception of the West, sales activity rose during the month, with the largest increase in the Northeast. Consistent with weakness in housing starts and existing home sales, new home sales in the West declined during the month. The broad trend across various housing indicators would suggest steady, modest improvement.

Durable Goods: New orders for durable goods increased 3% in October, a gain that represented a big jump in the volatile aircraft category and a modest pickup elsewhere. Through the first 10 months of the year, durable-goods orders were down 4.2% compared with the same period in 2014. The downturn reflected reduced demand due to low oil prices, a strong dollar and slow overseas growth. The trends also pointed to ongoing business-investment sluggishness as global headwinds and low oil prices have continued to weigh on new economic activity.

Fed: The market seems to believe the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates in December as long as job growth and inflation trends don’t take a turn for the worse before their next meeting. Since the Fed’s October gathering, economic data have generally supported the central bank’s view that the job market has improved and wage and inflation pressures were slowly and gradually starting to build. The unemployment rate dropped to 5%, half the recent peak it reached in 2009. Broader measures of unemployment accounting for discouraged and part-time workers, have also receded.

There are a number of reasons for the Fed to act soon on rates. These reasons would include the risk of creating uncertainty in financial markets by holding off again, the risk that financial market excesses keep building if rates are kept too low for too long, the risk of signaling the Fed lacks confidence in the economy and the risk of not accounting for cumulative gains already achieved in the economy.

Looking ahead, other factors could keep downward pressure on interest rates including low productivity growth and an aging population with lower consumption needs. As a result, the path of future interest rate increases should prove to be very gradual.

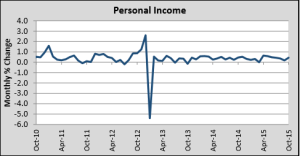

Income: U.S. consumers have grown increasingly cautious ahead of the holiday shopping season, a potential drag on economic growth during the final months of the year. Last month, Americans put away much of their income from rising wages, pushing the personal savings rate to its highest level in nearly three years. It wasn’t clear whether October was a one-month blip—setting up a holiday spending splurge—or a broader pullback amid mixed economic signals at home and trouble overseas. The data would indicate that consumers have become increasingly aware of economic crosscurrents in the domestic as well as the global economy. That may include sensitivity to layoffs across the energy sector brought on by low oil prices, struggle among manufacturers weighed down by a strong dollar and tepid overseas demand, terrorist attacks in Europe and strife in the Middle East.

Personal consumption climbed only 0.1% in October from a month earlier, the same slow growth as in September. Personal income rose a healthier 0.4% in October, led by gains in dividends, rental income and wages. Rather than spend, though, Americans decided to put away more money. The personal saving rate, which measures the share of a person’s disposable income saved was 5.6% in October, the highest level since December 2012.

The personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price deflator increased by 0.1% last month, with the year-over-year measure unchanged from the previous month at 0.2%. The core PCE deflator (excluding food and energy prices) was flat in the month while the year-over-year measure of the core PCE deflator remained at 1.3% for the tenth consecutive month.

On the bright side, income growth picked up on strong wage and salary gains which were up 0.6% m/m – their fastest pace in five months. This would suggest that the improvement in the labor market, recently manifested in a pick-up in average hourly earnings, has definitely ended up in consumers’ pockets. On the other hand, consumers appeared cautious about spending that windfall, with real consumption decelerating to its slowest pace since snow-impacted February. Given the strong gains in income and low gasoline prices, consumers hopefully will spend some of this windfall during the upcoming holiday shopping season to drive economic growth.

Corporate Profits: Profits at U.S. companies during the third quarter posted their largest annual decline since the recession, underscoring the competitive pressure from a strong dollar and weak global demand which has limited businesses’ ability to support stronger economic growth through capital expenditures. Earnings adjusted for inventory and depreciation dropped to $2.1 trillion in the third quarter, down 1.1% from the second quarter. Compared with a year earlier, profits fell 4.7%, the biggest annual decline since the second quarter of 2009. Weak profits could weigh on future business investment, put pressure on stock prices and pose a challenge for Federal Reserve officials who have been trying to raise interest rates after seven years of near-zero rates.

U.S. companies’ profits plunged during the recession then rebounded in the early stages of the recovery. But they’ve been trending lower for years, a reflection of slow growth abroad and moderate growth at home. Profits as a share of overall economic output have shrunk to 11.4% in the third quarter from a recent peak of 12.5% in 2012.

The latest reading highlighted the divergence between domesticallyoriented operations and U.S. companies’ overseas operations, where the stronger dollar has effectively made U.S. products more expensive and global weakness has undercut demand for U.S. goods and services.

The decline in profit growth has also tracked slower real final sales of domestic product, a key measure of underlying demand for goods and services in the economy excluding changes in inventories. The decline in profit growth increased at only a 2.7% pace in the third quarter, down from an earlier estimate of 3% growth. Softness in the corporate sector means the Fed may need to stick to an even lower trajectory of rate increases in the coming years.

Investors: Financial-market sentiment towards an interest rate increase has been strong and the Fed risks losing credibility if it were to surprise investors again by standing pat. Expectations for higher rates have driven investment flows into U.S. assets, pushed up short-term bond yields in the U.S. and reignited a rally in the dollar. Higher U.S. yields have bolstered foreign investors’ demand for long-term U.S. government debt, keeping a lid on a rise in yields.

At the same time, the European Central Bank and many other global central banks have made clear they expect, in coming months, to pursue easier policies to bolster their anemic economic growth, which has pushed rates down already.

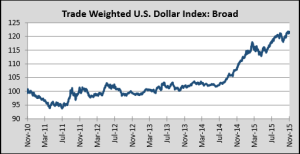

U.S. Dollar: Expectations that the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates for the first time since 2006 have fueled an autumn dollar revival. The U.S. dollar was up 5% against the euro and 2% against the yen since the start of October, when riskier assets such as emerging-market stocks and bonds began staging a strong recovery from August’s global-growth scare.

Commodity prices have slumped over the same period, reflecting deepening concerns about hefty supply and the appetite from the world’s largest consumer of many raw materials, China. Continued dollar gains will likely add to the downward pressure on oil and other commodity prices as globally traded commodities are priced in dollars. Ripples from the dollar’s rise were evident in late 2014 and early this year, when emerging-market currencies and other commodity-related assets were battered.

Adding to the dollar’s attractiveness, the European Central Bank appears to be on the verge of easing monetary policy, a move that would likely push down the euro and further bolster the dollar. Investors often seek out countries where interest rates are rising.

A stronger dollar should hurt U.S. exports and shrink the value of revenues U.S.-based multinational companies earn from overseas operations. It would also threaten to deepen economic malaise in many developing nations, where firms that used cheap dollardenominated debt to expand during the commodities boom are now struggling with soft revenue and rising costs.

Europe: The economic recovery in the euro area has continued but the pace has been slowing of late. Growth had picked up to 0.5% in the first quarter of 2015 (compared with the final quarter of 2014), the perkiest since the upswing started in the spring of 2013. Since then, however, it has slackened to 0.4% in the second quarter and 0.3% in the third. That pace has been disappointing given the fact that the euro area has benefited from a double boost. First, the fall in energy prices has acted in much the same way as a tax cut, boosting consumer spending – the main engine of the recovery. Second, the European Central Bank has been conducting quantitative easing – creating money to buy financial assets – since March. Among other things this has kept the euro weak, helping Eurozone exporters and contributing to a big current-account surplus of 3.7% of GDP in 2015.

Looking ahead, the euro area is likely to maintain a steady if unglamorous pace of recovery reflecting two conflicting forces. On the one hand, the slowdown in China and emerging economies, which account for a quarter of eurozone exports, will hurt exporting companies. Germany will be particularly affected since the Chinese market has been a lucrative one for Germany’s exports of investment goods and luxury cars. Already, German industrial orders have been falling while industrial production declined in the third quarter. On the other hand, the European Central Bank is poised to loosen monetary policy further when its governing council meets in December. Finally, spending on refugees, especially in Germany, will provide a modest fiscal stimulus.

Global Economy: After coasting for years on support from their central banks, top economies are struggling to come up with viable steps to reshape an increasingly weak outlook. They are also facing a host of new troubles, from political problems to security crises, clouding the horizon and raising doubts about the ability to keep the world economy from falling into a long-term decline. China’s slowdown and turmoil across emerging markets have heightened worries for months. Now, a growing refugee crisis in Europe has been sapping attention from underlying economic problems already proving difficult to fix.

Facing a global crisis in 2009, the G-20 became the world’s economic executive board and managed to coordinate a powerful policy response with government spending and central-bank support. But since then, these countries have struggled to jump-start anemic output and their coordinating abilities have strained their limits to constructively intervene. The flood of government stimulus that helped boost economic growth in 2009 turned a global recession into an expansion by 2010. But it has also pushed debt levels to dangerous levels, leaving little inclination for new spending.

Central banks in advanced economies have been getting less bang for their bond-buying buck. They have also found it harder to stimulate credit-fueled growth as interest rates test their lower limits. Some countries have even tried pushing interest rates into negative territory, charging depositors for keeping money in accounts as they attempt to spur spending and investment.

High debt levels have left little appetite for boosting government spending. Although budget deficits have recovered from their most toxic levels, they are still twice pre-crisis levels in rich countries. Even as Europe tries to recover from its own debt crisis, an influx of refugees has been putting new pressure on budgets.

Meanwhile, the primary engine of world growth coming out of the financial crisis—emerging markets—will face a host of problems constraining their ability to act. Plummeting commodity prices, China’s slowdown and investor flight are exposing deep-rooted weaknesses. Many countries have reached the limit of their capacity to expand without fundamental economic overhauls. But domestic politics will make such restructuring difficult. With a few exceptions, those headaches have left them largely bereft of cash needed to jump-start demand.

Before the 2009 global recession, emerging-market governments on average ran budget surpluses. Now, those governments have dug themselves into an average budget deficit worth 4% of gross domestic product. General debt levels in those countries has also ballooned. With such a dour outlook across the globe, the world is now largely relying on the U.S. as the consumer of last resort.

(Sources: The Conference Board, the Labor Department, the Commerce Department, National Association of Realtors, European Central Bank.)